Markus Petteri Laine University of Greenwich 2004<?xml:namespace prefix = o ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" />

ABSTRACT

Eastern and Central Europe is in transition. This paper shows that Central and Eastern Europe Countries (CEECs) have mostly achieved the requirements of formal democracy, how ever they still have a long work ahead in bringing their societies institutions and citizens' networks to the level of the Western standards.

This paper drafts a quick look into CEECs societies and their near historical development and key problems after the revolutions that threw the former one-party systems to history in 1989. It shows that the CEECs transition is not only a local transition, nor is it only a transition towards democracy but it is rather a part of global transition towards neo-liberalistic markets and global networking of institutions. The era of CEECs transition towards democracy is becoming into an end.

DEFINITION OF DEMOCRACY

Ever since democracy became the subject of political philosophy and political theory there have been varying definitions and usages of the term.[1] 'George Orwell noted:

'In the case of a word like democracy not only there is no agreed definition but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides The defenders of any kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning.'[2]

There have been many attempts to define the criteria for democracy. Mary Caldor and Ivan Vejvoda[3] have adapted Robert Dahl's originally drafted list of formal criteria 'procedural minimal conditions'.[4]

1. Inclusive citizenship: exclusion from citizenship purely on the basis of race, ethnicity or gender is not permissible.

2. Rule of law: The government is legally constituted and the different branches of government must respect the law, with individuals and minorities protected from 'tyranny of the majority'.

3. Separation of powers: The three branches of government legislature, executive and judiciary must be separate, with an independent judiciary capable of upholding the constitution.

4. Elected power-holders: Members of the legislature and those who control the executive must be elected.

5. Free and fair elections: elected power-holders are chosen in frequent and fairly conducted elections, in which coercion is comparatively uncommon and in which practically all adults have the right to vote and to run for elective office.

6. Freedom of expression and alternative sources of information: citizens have a right to express themselves on political matters, broadly defined, without the danger of severe punishment, and a right to seek out alternative sources of information: moreover, alternative sources of information exist and are protected by law.

7. Associational autonomy: Citizens also have the right to form relatively independent associations or organizations, including independent political parties and interest groups.

8. Civilian control over the security forces: The armed forces and police should be politically neutral and independent of political pressures, and under the control of civilian authorities.

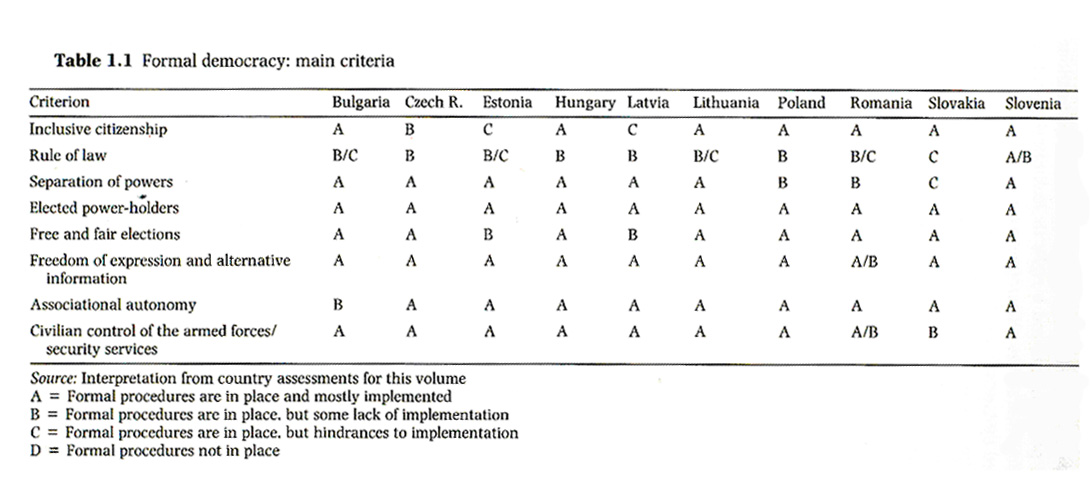

Table1 summarizes the findings from Mary Caldor's and Ivan Vejvoda's study about the extent to which the CEE countries (Central and East European Countries - CEECs) meet the formal criteria of democracy as defined above. Caldor and Vejvoda found that by and large the ten CEECs do meet the formal criteria for democracy.[5]

TABLE 1. FORMAL DEMOCRACY: Main criteria

The extent to which a particular society can be said to be characterized by a democratic political culture in which there is a genuine tendency for political equalization and in which the individual feels secure and able and willing to participate in political decision-making is not something that can be easily measured.[6]

POST-COMMUNIST POLITICAL MODEL

Most of the CEECs have made a definitive break with the communist past. The formal rules and procedures for democracy are more or less in place. In all the CEECs there have been peaceful alternations of power. No one is punished for his or her political views, although arbitrariness and insecurity persist, especially for minorities. Access to alternative sources of information is beginning to spread beyond urban centres.[7]

The monopoly of power that used to be by the communist parties has been replaced by the dominance of single parties, in most cases the reformed post-communist party, often associated with a single personality, or a grand coalition. Both post-communist and new political parties have a tendency to extend control over various spheres of social life. While the media are in principle free, the broadcast media tend to be dominated by the government. Government tends to be top down and centralizing. The notion of a public service tradition in the media, administration or police forces is under developed; many former apparatchiks have transformed themselves into the owners of the newly privatized enterprises. There remains in some countries a widespread sense of insecurity and lack of trust in institutions. There is very little substantive public debate about such issues as education, economic policy and foreign policy.[8] In several countries there is sharp political polarization. The post-communist parties' aside, membership of political parties is low, as it is participation in public debates.

CEECs transition is not just a transition to democracy. It is a transition to the market, a transition from cold war to peace, a transition from Fordist mass production to the information age, and for several countries the Baltic states, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and Slovakia a transition to renewed or new forms of state hood.[9]

All the CEE societies under discussion are truly pluralistic, heterogeneous societies composed of people of widely diverse perspectives and ideologies, even if not always diverse ethnic and religious traditions.[10]

EXTERNAL FACTORS OF TRANSITION

All the CEE societies presented in TABLE 1 are truly pluralistic, heterogeneous societies composed of people of widely diverse perspectives and ideologies, even if not always diverse ethnic and religious traditions.[11]

Historical legacy, the liberal-democratic ideological paradigm, and the forces of globalization have had enormous external impact on democratic consolidation in CEE countries.[12]

The free flow of ideas across Eastern borders exposed these countries to the liberal democratic values which have dominated global discourse over the last decade. The opening of markets may well have contributed to the rise of international economic crime and even to massive financial crashes in some countries. But in other cases liberalization stimulated economic rationalization, and even produced astounding economic growth. What ever the balance of positive and negative effects, globalization was largely responsible for four important developments relevant to our discussion.

First, and most obviously, globalization has eroded the sovereignty of the new democracies in the region.[13]

Secondly, globalization has forced the new democracies of Eastern Europe to attempt constructing a new type of 'competition state', to use Philip G. Cerny's expression.[14]

States that failed to become competitive experienced full-blown institutional collapse, as experienced in Russia, Ukraine, and Albania. Those that that succeeded in becoming competitive Poland, Hungary, Estonia, Slovenia and the Czech Republic enforced the decisions made by world markets, transnational private interests, and international quango-like regimes. ('Guango' or quasi-autonomous non-governmental organization, is an authorative body licensed by the state or government to carry out public regulatory functions but made up of appointed representatives of private sector interests; a variant of state corporatism.[15]

Thirdly, globalization has induced the new democracies of Eastern Europe to cooperate with international institutions responsible for organizing global order and coping with transnational pressures. Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, the European Union, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development have been helping these states to take advantage of globalization rather than fall prey to its ill-effects. Cooperation with these international institutions is seen frequently as a sign of the desire to return to Europe and the Western world after years of living under Soviet yoke. That said, conditions imposed by the EU or the IMF leave little space for domestic considerations and create the impression that crucial decisions are not been made in national parliaments but rather in Washington DC or Brussels. The scope of this external 'intervention' should not be underestimated. Countries aspiring to join the European Union, for instance, have been asked to fully implement the acquis communautaire which contains some 20.000 laws and regulations covering a wide range of issues in both the public and private spheres.[16]

Fourthly, globalization has stimulated the reorganization of the political space in Eastern Europe. The division between these parties of 'globalization' and 'territoriality', to use Charles Maier's words, cuts across traditional party lines and ideologies.[17] Although all eastern European states have been affected by globalization, this does not mean that the state has become marginal. The cases of Russia and Ukraine clearly show that meaner, more repressive modes of state organization are being adopted to prevent the collapse of public institutions which are unable to live up to the challenge of globalization.[18]

Whether a country drifts toward democracy or autocracy is not only a function of actors' policies, but also of broader historical, ideological and economic processes at work. These processes are not simply a product of rational calculations or meticulously conceived designs. In fact, they are seldom controlled by any single government or international organization.[19]

The dominance of market based, Western-style democracy has effectively ended the debate on alternative models of democratic governance which might be better suit the complex post-Soviet and largely pre-modern environment of Eastern Europe. Some even argue that the neo-liberal economic prescription behind the so-called 'Washington consensus' was indifferent to, if in not conflict with, democratic ideals.[20]

To understand democratic developments in Eastern Europe we certainly need to rely on both empirical work conducted by country or region specialists, as well as theoretical work conducted by transitologists and democratic theorists.[21]

INSTITUTIONAL ENGINEERING

Institutions matter in the sense that they are not neutral; they do not merely channel and organize pre-political forms of collective life. Rather they crucially affect, influence, and change the way politics develop. They importantly constrain the range of choices available to public actors, they organize patterns of socially constructed norms and roles, and they define the prescribed behaviours that those who occupy those roles are expected to pursue.[22]

Wojciech Sadurski concludes that[23]:

"Any attempt to attribute a particular difference in institutional patterns to a relevant difference in the tradition, forms of civil society, economic development, or any other non-institutional factor within any of the CEE countries would be extremely risky. Any attempt at a generalisation of this sort could be negated by counter- examples. And this, in my view, supports a thesis that institutions often determine, rather than are determined by, the events of history."

The constitutionalization of politics in Central and Eastern Europe has been a powerful factor in strengthening (though not initiating) the process of transition to democracy in that region.[24]

Proff. Daron Acemoglu MIT argues that institutional organization level and security of property rights are key conditions for national prosperity[25]:

"Institutions---organization of society, "rules of the game"--- are a major determinant of economic performance and a key factor in understanding the vast cross-country differences in prosperity... ...Institutions are not exogenous, but there are potential sources of exogenous variation in history. Example: the "natural experiment" of European colonization and use of history to estimate the causal effect of institutions on growth.

...If political power is the monopoly of the few, the property rights of the rest cannot be entirely secure. Conversely, if economic institutions lead to unequal distribution of resources, political institutions cannot be democratic. Institutions matter. Although ideology and history influence institutions, in many cases institutions emerge because of their distributional consequences."

TOWARDS EUROPEAN UNION AND GLOBALIZED MARKETS

Several of the characteristic of the post-communist model can be found in Western countries, albeit in weaker form. These include the relative paucity of substantive debate, growing apathy, and cynicism about politics, the reliance on media images instead of reasoned persuasion, and increasingly top-down approaches to politics. It is possible to speculate about the reasons: The limited space for manoeuvre for national governments in an increasingly globalized and interdependent world; the difficulty of departing from the pervasive neo-liberal ideologies promulgated by international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank; and the growing power of the broadcast media. One important explanation could perhaps be the absence of a forward-looking project after the discrediting of earlier utopias; hence the preoccupation with the past.[26]

Mary Kaldor and Ivan Vejvoda argue that what is required, is the construction of a European public sphere in which critical voices from different parts of Europe and at levels of society have access to policy-making and can help to define the 'democracy mission'. Essentially this means the development of networks called 'active solidarity',

(by the former European Commission Jacques Delors 1995), interdependencies for the democratic practice of justice, networks based on ideas rather than issues.[27] Such networks would need to involve a range of social actors in co-operative and transnational forms of discourse. Pan-European networks already exist as a result both of the official political level and of various academic and cultural exchanges, but they tend to be confined to elites. The question is how to reach out beyond elite networks to, for example, local community organizations, women's groups and young people.[28]

Marcin Krol states: The Tragedy for Central and Eastern Europe lies in the fact that its pre-democratic crisis coincides with Western Europe's post-democratic crisis.[29]

There are, however, certain positive tendencies, shafts of light which illuminate this somewhat gloomy depiction of democratization in the CEECs. One is the dramatic growth of both voluntary organizations NGOs, civic groups etc. and small and medium-sized enterprises. It sometimes occurs in partnership with local and regional levels of government and is often linked to international networks as a result of the growing ease of travel and communication. This is a phenomenon to be found in both East and West, and it opens up the possibility of a new kind of democracy-building from below, provided political and financial limitation on local and regional autonomy can be overcome.[30]

The commitment to eventual EU membership, conditional to certain (qualitative) economic and political criteria is fulfilled, was made between EU and CEECs at the Copenhagen European Council in June 1993.[31]

The European Union is now preparing for its biggest enlargement ever in terms of scope and diversity. 13 countries have applied to become new members: 10 of these countries - Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia are set to join on 1st May 2004. Bulgaria and Romania hope to do so by 2007, while Turkey is not currently negotiating its membership.

In order to join the Union, they need to fulfill the economic and political conditions known as the 'Copenhagen criteria', according to which a prospective member must:

Be a stable democracy, respecting human rights, the rule of law, and the protection of minorities; have a functioning market economy; adopt the common rules, standards and policies that make up the body of EU law.[32]

As the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia are set to join EU on 1st May 2004 the concept of Central and Eastern European countries is once again changing. Crucial division among the former East European communist countries is made when one part of them are joining the EU. The question remains what will happen to the other half. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Albania haven't been even mentioned in Western public discussion as potential EU member states, even though their cultural roots lie in Europe as solidly as any other EU member states. The global economic pressure will keep on pushing them in to the reform as well.

CONCLUSION

Even though CEECs are taking baby steps in liberal democracy the pace of change from communist one-party system has been rapid. The fruits of transition in to democracy are already been collected. Integration to the EU is taking place for most of the CEEC countries in May 1. 2004. Never before in the World's history has Europe been as peacefully united as today.

The Outcome of this union affects the whole global community as well as regional societies. CEECs ability to adjust their local institutions in the way that they serve their citizens the best possible way becomes crucial factor in determining their competence in the global markets, and how fast CEEC citizens can develop efficient connections and networks in their societies, as well as in the international community. NGOs have already flourished now it is in the CEECs best interest to build trust in to the national institutions and to bring efficiency and genuine authority to the local governments.

If the beginning of the transition era towards democracy can be allocated around the revolutions of 1989 then we could say that this era is coming to an end when main body of CEECs is joining EU. This does not mean that development of democracy would be complete in the region. It rather suggests a dawn of a new era, where CEECs and the current EU member states democratic future is legitimately combined.

CEECs are in their way to European integration, global institutional networks, westernized consumer culture, global economy and a more liberal democratic way of living.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Juan J. Linz 1978 The Break- down of democratic regimes. Crisis, Breakdown, and Reequilibration (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press. p.8)

George Orwell (1957, p. 149

Mary Caldor and Ivan Vejvoda, Pinter 1999 p.4 Democratization in Central and Eastern Europe

Robert Dahl 1982, p.11. Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

I. Vejvoda 1996 'Apotilisme et postcommunisme'. Tumultes, 8, September

Schopfling .G (1994) 'Post communism: The Problems of democratic construction'. Daedalus, Summer

Democratic Consolidation in Eastern Europe Vol.1. Several contributors Edited by: Jan Zielonka. Wojciech Sadurski: 'Conclusions on the relevance of institution and the Centrality of Constitutions in Post-communist Transitions. Oxford University Press, 2001

Jan Zielonka and Alex Pravda: Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe Vol.2 International and Transnational Factors, Oxford University Press 2001

Csabe Gombar, Elemer Hankiss, et al., The Appeal of Sovereignty: Hungary, Austria, and Russia (Boulder, Colo.: Social Science Monographs, 1998).

Philip G. Cerny, 'Paradoxes of the Competition State: The Dynamics of Political Globalization', Government and Opposition, 32: 2 (1997)

Charles S. Maier, 'Territorialisten und Globalisten: die beiden neuen "Parteinen" in der heutigen Demokratie', Transit, 14 (Winter 1997)

Peter Evans, "The Eclipse of the State? Reflections on Stateness in an Era of globalization', World Politics, 50 :1 (Oct.1997)

Joseph E Stilitz, ' Whither Reform? Ten years of the Transtion'. Paper prepared for the Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, Washington ) 28-30 Apr.1999). Available at http://www.worldbank.irg/research/abcde/stiglitz.pdf).

Robert E. Goodin, 'Institutions and their Design', in Robert E. Goodin (ed.), The theory of Institutional Design (Cambridge university press, 1996)

Proff. Daron Acemoglu MIT (based on joint work with Simon Johnson and James Robinson) Lionel Robbins Lectures, London School Economics, Feb.23-25 Understanding Institutions. Available in PDF (30 March 2004) at: